Will women make their own decisions, or will government decide for them?

For decades, abortion has been a get-out-the-vote issue for Republicans, but not so much for Democrats. After all, as long as the Supreme Court was there to protect your rights, what practical difference could an anti-abortion legislature or Congress make?

But now that Trump’s three appointees have taken their seats on the Court, women’s rights (and privacy rights of all kinds) are up for grabs again. If you want to defend those rights, you have to vote.

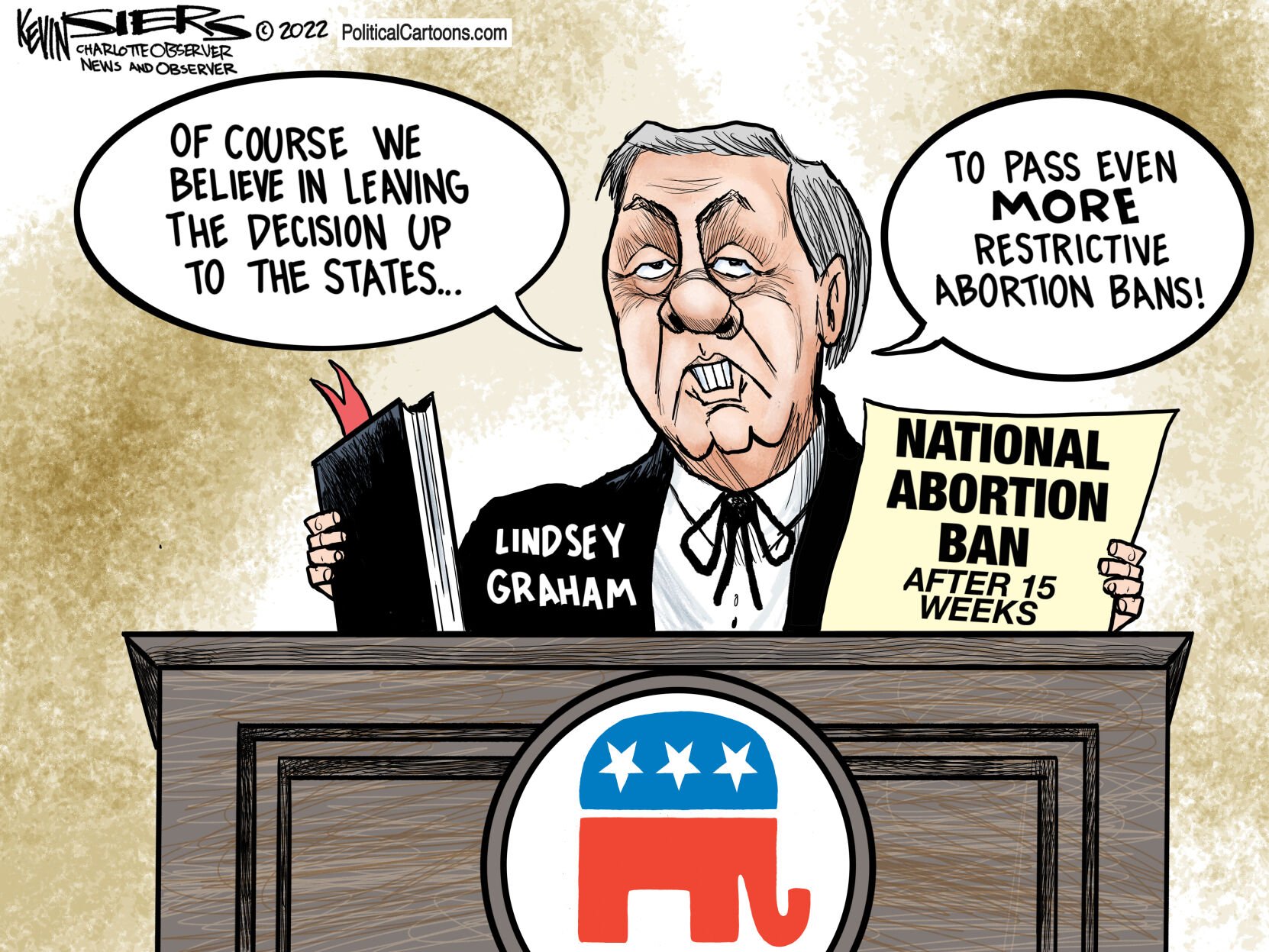

The two parties’ positions. Last June’s Dobbs decision has allowed states to pass some truly horrible laws that not only deny women’s bodily autonomy, but even put their lives in danger. Initially, Republicans claimed the Court had simply returned the abortion question to the states, implicitly promising that women in blue states would keep the rights they had before Dobbs. But now many are pushing for a national abortion ban.

If history is any guide, Republicans who haven’t publicly supported such a ban — and perhaps even some who have taken a stand against one — will get in line once it comes up for a vote. Few GOP congresspeople have the backbone to stand up against the anti-abortion movement, and even fewer have shown a willingness to buck Donald Trump. So if a bill is on the floor and Trump is pushing them to support it, what do you think they will do?

By contrast, Democrats support a law that would restore the rights women lost when Roe was overturned.

“Why haven’t they already passed it?” is a fair question. Such a law has passed the House, but fell one vote short of a majority in the Senate. Two Democratic senators haven’t been willing to create an exception to the filibuster that would allow a majority to pass the law. But if Democrats gain two seats in the Senate — say, if John Fetterman replaces Pat Toomey in Pennsylvania and Mandela Barnes replaces Ron Johnson in Wisconsin — the law will pass and President Biden will sign it.

What’s wrong with the state abortion bans? The best argument against the various state abortion bans is to look at specific examples of what they’ve done.

The case that got the most publicity was when a raped 10-year-old had to leave Ohio and go to Indiana to get an abortion. (Indiana has since passed a ban nearly as extreme as Ohio’s, but it does have a rape exception. That law is being challenged in state courts.)

But while they may appear comforting, the exceptions in state abortion bans often provide little protection in practice. The ban in Texas, for example, includes an exception to protect a pregnant woman’s life. But when Amanda Zurawski found out that her fetus was not viable and that continuing to carry it was dangerous, all she could do was wait. The fetus wasn’t dead yet, and she wasn’t dying yet, so under the law, nothing could be done. She describes her experience like this:

People have asked why we didn’t get on a plane or in our car to go to a state where the laws aren’t so restrictive. But we live in the middle of Texas, and the nearest “sanctuary” state is at least an 8-hour drive. Developing sepsis—which can kill quickly—in a car in the middle of the West Texas desert, or 30,000 feet above the ground, is a death sentence, and it’s not a choice we should have had to even consider. But we did, albeit briefly.

Instead, it took three days at home until I became sick “enough” that the ethics board at our hospital agreed we could legally begin medical treatment; three days until my life was considered at-risk “enough” for the inevitable premature delivery of my daughter to be performed; three days until the doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals were allowed to do their jobs.

By the time I was permitted to deliver, a rapidly spreading infection had already claimed my daughter’s life and was in the process of claiming mine.

I developed a raging fever and dangerously low blood pressure and was rushed to the ICU with sepsis. Tests found both my blood and my placenta teeming with bacteria that had multiplied, probably as a result of the wait. I would stay in the ICU for three more days as medical professionals battled to save my life.

Mylissa Farmer tells a similar story. Her fetus was dying and her own life was in danger, but she wasn’t quite sick enough yet for doctors in Missouri to help her. She had to travel to Illinois for treatment.

Since their ordeal, Farmer has lost trust. While she still feels her obstetrician at Freeman Hospital in Joplin is a good doctor, she’s worried about whether medical professionals in Missouri will be able to offer patients necessary care.

“I haven’t lost trust in care, but I’ve lost trust (doctors) will be allowed to make the medical decisions they need to make,” she said.

She’s lost trust in the politicians who represent her, as well.

Despite reaching out to various legislators, she has yet to receive an answer that satisfies her: Why is this law written this way? If it’s to protect women, why did she have to be in danger before she could get care in-state? Why is it such a binary law?

“The world is too nuanced to put such strict rules in place,” Farmer said.

Farmer’s story is not unique. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, preterm premature rupture of membranes happens in 2% to 3% of pregnancies in the United States, and leads to preterm birth in one out of four cases.

Imagine if a similar law were in place nationally. Where would women like Farmer go then?

The new laws treat other health dilemmas with similar disdain. Imagine discovering, shortly after you miss your first period, or perhaps during a prenatal physical, that you have cancer. Chemo-therapy and radiation can seriously harm or even kill a fetus. So what’s the alternative? Wait until the baby is born, and hope that your cancer is still treatable by then? If you’re not facing immediate death, that could be the only legal option. No wonder an article in the journal Demography concludes:

Overall, denying all wanted induced abortions in the United States would increase pregnancy-related mortality substantially, even if the rate of unsafe abortion did not increase.

Who decides? Pro-life rhetoric tends to gloss over such complexities. Pregnancies are problem-free, loving families are lined up to adopt even the most damaged newborns, and so the right thing to do is obvious. All we need is a law to make women do it.

But once you admit that there are any valid exceptions, then someone has to decide which individual cases are exceptional enough to qualify. Republicans believe that those decisions should be made by legislatures, or perhaps by hospital lawyers trying to avoid liability under laws the legislature left vague.

Democrats believe those decisions are best made by the people involved: the pregnant woman, advised by her family, her trusted friends, and the best medical and moral advisors she can find. This is especially true when there are significant risk-tradeoffs to weigh. Take the cancer example: Some women may feel so committed to the life growing inside them that they don’t hesitate to risk their own lives. That decision could be heroic, but the law should not force heroism on people.

And I can easily imagine a husband protesting against heroism: “I’m not ready to sign up for a future where you die and I’m left to raise a child by myself.” Those kinds of discussions need to happen inside families, not in Congress or in front of a hospital ethics board.

Religion. Most abortion decisions are not driven by health considerations, but by how a woman pictures her life proceeding with or without a child, and how she frames the moral questions abortion raises.

Different individuals and different religions see those questions differently. Some (but not all) Christian sects believe that a fertilized ovum already has a human soul, and that killing it is murder. Some (but not all) Jewish sects believe that the soul enters the body much later, perhaps not until the first breath. (See the creation of Adam in Genesis 2:7.) Other religions and non-religious people’s opinions are all over the map. Most Americans appear to believe that the moral status of a fetus starts low and increases as it develops, which is why few people worry much about fertilized ova frozen in fertility clinics.

Whose opinion should control? Consider that if you ate a hamburger yesterday, a Hindu might tell you that the steer it came from had a soul every bit as significant as your own, one that may have inhabited a human body in a previous incarnation. Should this Hindu theology limit what you can eat?

Democrats believe that disputed religious questions should be decided by individuals, and that, unless the government has a secular reason to intervene, your behavior should be governed by your own beliefs (or lack thereof). Republicans believe that conservative Christian theology should control everyone’s behavior, a position they sometimes call “freedom”.

Late-term abortions. Anti-abortion activists believe late-term abortions are their trump card. In one typical attack, the National Republican Senatorial Committee claims “Radical John Fetterman Supports Abortion Up Until the Moment of Birth“. The headline conjures up an image of Fetterman (or any Democrat) actively supporting abortion, as if he recommends that women get abortions and tries to persuade them to do so.

But nothing remotely like that is actually happening.

What most (not all) Democrats believe is what I said in the previous section: The decision whether or not to have an abortion can be difficult, and is best made by the people involved rather than by the government. Republicans, on the other hand, believe in some absolute cut-off: After some number of weeks, the government’s judgment automatically becomes better than the family’s. Your case is exceptional if the government says it’s exceptional.

In fact, late abortions are precisely the situations where the government’s arbitrary rules have the least to offer. Such abortions are rare (about 1% of all abortions take place after 21 weeks, and far fewer after 24 weeks), and almost every one is a unique story in which something has unexpectedly gone wrong with a wanted pregnancy. (Though many abortions near the deadline take place because jumping through anti-abortion hoops can delay a poor woman, who may have trouble assembling the resources she needs to travel to a distant city and stay there through a waiting period.)

The Guardian quotes one woman’s husband:

For those who believe these babies are unwanted, Matt says: “You’re not going to wait until halfway through your pregnancy to finally have an abortion.”

I can think of no better closing than to repeat what Mylissa Farmer said:

The world is too nuanced to put such strict rules in place.